I’m actually not sure what to start off with for this blog post.

I suppose first, I’ve been without electricity for the past four days now, and despite having filled out a maintenance form every single day, nobody has come to fix it (although workers have come to my building to fix other things)… In any case, I’ve essentially gotten used to this rustic living. My body has adapted to being without AC, without hot water, and without a washing machine. Meanwhile, I’ve been charging my phone at restaurants and other public spaces. My battery, now at 50%, has sat off the entire weekend because I wanted to make sure I could use it as needed. Although, since I have class tomorrow morning, it should be fine to use it now and charge it in class—I hope.

Now, let’s move on to the more interesting things that have been happening. Yesterday, I took the bus and went to my first guqin lesson. The bus ride there was absolutely terrifying—I felt like I was on a roller coaster rather than a bus, complete with sudden lurches, abrupt stops, and a cacophony of car horns.

Now, the guqin lesson itself was rather straightforward. However, it wasn’t without its surprises. When I walked in, I noticed a proudly-framed photo of my new instructor standing next to Ven. Master Hsing Yun. Small world. I sat down and my instructor started me on the basic hand techniques. As I practiced, he’d chat about my experience in the US, and how odd it is for someone from the US to want to learn guqin.

This cozy space leads up to the classroom.

But just so you get a feel for how old this building is, here’s a view of the ceiling.

I had just finished explaining that I would only be in China for year when he stopped abruptly.

“One year…” he muttered.

He came over and stared at me, “You’re going to have to take extra classes every week, but I’ll get you up to speed. I want you to go back as someone who can claim this lineage.”

I stared back at him, absolutely taken aback by the kung-fu movie-esque exchange. “I would love to take extra classes.”

“I’m serious,” he continued. “It would be really good to have someone who can play guqin in the US. I want you to learn something that typically takes people three to five years to learn—but you only have ten months. You’re going to be practicing at least one to two hours a day. If you’re not ready to commit, it’s going to end up being a total failure.”

My mind jolted back and forth—hell, when would I ever get this opportunity again?

“I’ll do it.”

He laughed, “Alright. Now let’s see how you progress in the next week or two. Just because you can put in the effort doesn’t mean you’ll soak it up that fast.”

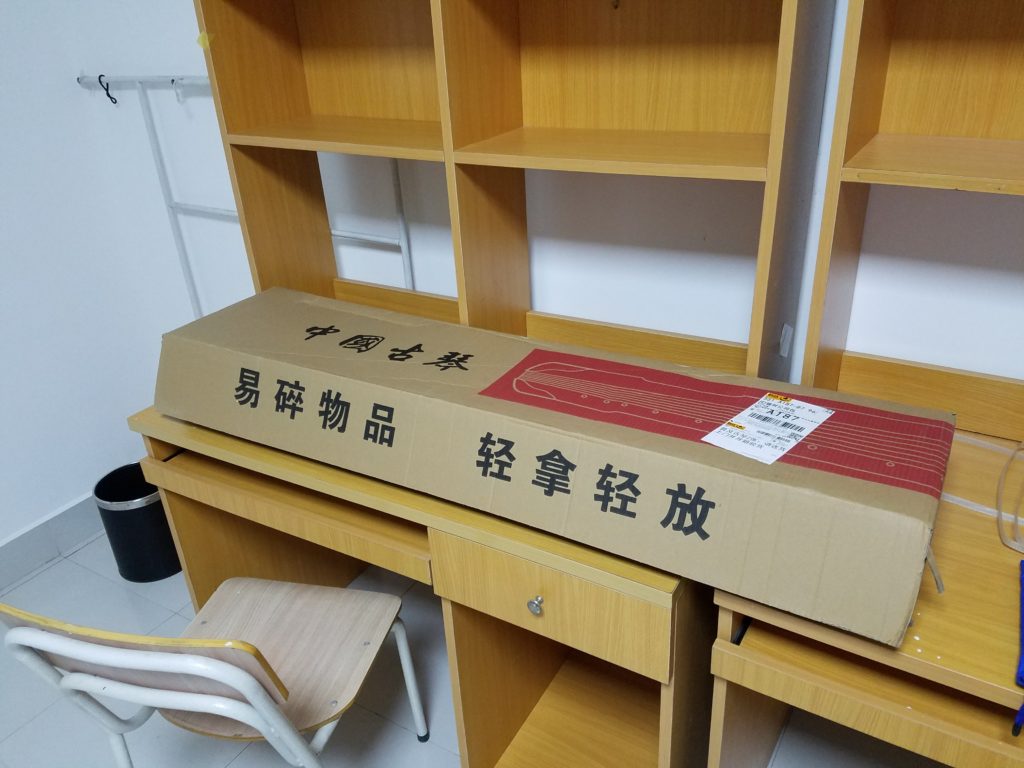

And with that, my guqin journey started. I left the classroom hugging a cardboard box with my new instrument inside and got home eager to play. He had given me instructions to learn three songs before my next class, which at that point was only 24 hours away.

Here’s the box it came in!

And here’s the cloth case. I can wear it on my back!

And the beauty itself.

And so I practiced.

Having not held a musical instrument since middle school when I was third chair of the four cellos in orchestra, I had completely forgotten how to read notation. Fortunately, it didn’t matter because guqin has a totally different notation system.

Playing a string instrument again brought back not so fond memories of painful fingers and the process of developing calluses (although truth be told, I never developed calluses in middle school because I never actually practiced at home).

Perhaps it’s because I’m more mature now, or perhaps it’s because I can play a song on my own rather than being relegated to playing some long C note for measures and measures, but while I still lack the hand-eye coordination to play guqin smoothly, it’s much more enjoyable than when I was playing cello.

At 10 pm, I decided to stop—I had memorized one song, completely failed at the second song, and could fumble my way through the third.

The next morning, I practiced for another two hours after breakfast, my fingers still raw from the night before. By the time I got to class, I had memorized one song, could fumble through the second song, and had parts of the third song memorized. Proud and ready to show my teacher my progress, I hopped on the bus.

The bus dropped me off on the side of the freeway, and after walking for 15 minutes in the blazing sun, I realized this was definitely not the right place. I walked back, cursing T-Mobile for failing in international data coverage. Using a combination of cached and screenshotted maps, I eventually found my way to where my class was supposed to be—except I couldn’t find an entrance.

After asking two local residents who had never heard of a class here, I decided to ask one more person: a college student walking up the hill.

“Hi, sorry to bother you, but do you know where Minjiang College is?” I asked.

“Yeah, you’re at Minjiang College right now—I go here,” she replied with a bit of confusion.

“Ok—so I’m taking a guqin lesson and it’s supposedly somewhere around here.”

“You sure? I’ve never heard of guqin lessons at this school.”

Well damn. I showed her the WeChat conversation in which my teacher specifically designated that this would be the location for our next class. She looked at it and thought to herself.

“Can’t you just message him and ask?” she seemed very confused.

“Unfortunately not. I don’t have a Chinese SIM card,” I admitted.

“Huh?” her confusion grew even greater, if that was physically possible.

“I’m from the US,” I explained. “I got here last week, and I don’t have a Chinese phone plan yet.”

“But… you’re not white,” she pointed out.

“I’m not. But not all Americans are white,” I replied.

She accepted my answer and kindly let me freeload off of her hotspot so I could call my instructor. He didn’t pick up.

“Well, instead of waiting in the heat, why don’t you come with me? If you’re into guqin, you must be into other traditional arts, right?”

“Yeah—do you do any arts?”

“Mhm, I’m training as a lacquer artist. It’s kind of dangerous though. The lacquer can trigger some really nasty allergic reactions.”

She pulled up her sleeve to show red blotches of irritated skin.

“Yikes.”

“Yeah, so feel free to look and ask me about stuff in the workshop, but do not touch anything.”

And with that, we walked up the hill and into the lacquer workshop where a few students and instructors were making trays.

“We mostly make export goods here,” my host explained. “Most of it goes to southeast Asia.”

As she showed me around, pointing out how lacquer is durable, light, and elegant, she gave me a brief overview of the different stages of lacquerwork, from the initial layering to decorating and buffing.

“Fuzhou has three treasures,” she said. “Bodiless lacquer—which is what we do—is one of them!”

“That’s cool! And what are the other two?”

“Dunno,” she replied. “I’m not a native Fuzhou-er.”

We laughed, and after watching them work, I finally got a response from my guqin instructor: wait there, I’ll pick you up.

I bid farewell to my wonderful host for the afternoon and walked back into the sun to see my guqin instructor standing outside. He was waiting for another lost student as well. We ended up walking towards the student dorms and entered what really was just a dorm. I suppose someone at the college must be a guqin fanatic and donated the space? The dorm resident popped in and out a few times, but like most college students just stayed on his computer in the quiet recesses of his room.

I left class with a note to return on Wednesday. I would take three classes per week and try to learn at least three years worth of material during my time here—if not more. In my conversations with my instructor though, I realized that this innocent hobby ties into my tea research a lot more than I had expected.

In terms of contemporary tea culture, there’s been a trend of viewing tea as a method of spiritual cultivation. While this perspective and function of tea can be traced back to Tang dynasty writings, it has reemerged with the “tea meditation” or 茶禪 aesthetic. This simple, no-frills way of serving tea is partly informed by Chinese interpretations of Japanese tea, but also an attempt to repackage tea for a modern “literati” lifestyle. That is, the geeks like me who live in the 21st century yet strive to learn arts like calligraphy, guqin, and tea appreciation.

In my guqin instructor’s elegant words: There is the Way of Tea, but music is also a way. To learn the way, you have to walk it—how long and far you walk determines where you end up.

To my instructor, guqin is an art that is also cultivation. In fact, his curriculum includes classical Chinese philosophy and neo-Confucian writings to balance practice and understanding.

While I’ll have to end this blog post here since it’s getting late, he mentioned a few other key points, one being the role of lineage in guqin circles. I’ll address this further in a later post. I’ll also update this post with pictures once I have stable electricity and internet.

The 古琴 is beautiful🧡 ! 👍

Glad to see the pictures!! You must show off your talents when you come home!