We visited Niushoushan the day after our trip to Dabaoen Temple, but I haven’t had a chance to write about it until now. A lot has happened in the past few weeks, and I will attempt to retell all of this chronologically.

Niushoushan was constructed in the early 2010s after the excavation of Dabaoen Temple revealed the Buddha’s skull relic. The construction, primarily funded by the Chinese government, is reminiscent of the imperial sponsorship that Changgan Temple (as it was previously called) enjoyed while it enshrined the Buddha’s relics.

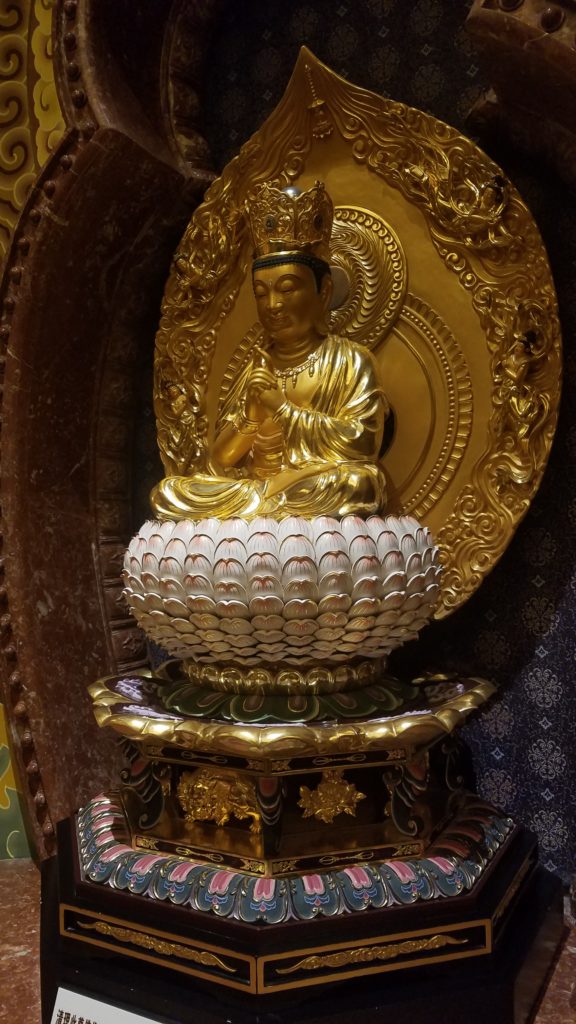

This new construction features a mix of modern, Indian, and East Asian architecture, drawing from cave temples and “Tang dynasty” aesthetics. Overall, it is a grand and impressive structure, but nonetheless I was rather disappointed.

It is—in all senses—a tourist attraction. There are no events, no services, not even an active monastic community. Adjacent to the majestic palace is a small monastery which houses a modest community of maybe ten monks who take care of the relics.

While the architecture is spectacular and the vision broad, there was not much in terms of research, and this led to quite a few errors in iconography. But again, this was constructed on a tight schedule and meant to be impressive rather than accurate.

By visiting this newly constructed site, a site meant to memorialize an integral part of Nanjing’s past grandeur, I noticed that these reconstruction projects are not very educational. They serve primarily to bolster national spirit and morale, exude pride in the greatness that China once embodied, and suggest that China’s current trajectory will restore it to that fantastic past.

I don’t mean to say that it is inappropriate for China to highlight its grand past. In fact, I appreciate that the country is rebuilding its past and letting the world see how majestic it once was. My issue with it comes from the inaccuracies that plague its presentation. I would enjoy it much more if, say, the spaces sought to replicate a particular time in Nanjing’s history.

Of course, every time we have modern architects reimagining what ancient Nanjing looked like, the most we will get is an architect’s imagination. It will never be fully accurate. However, there is still value in attempting to replicate and giving credit to the inspirations for the replication.

That being said, I think it is also interesting for an architect to have free reign and create this conglomeration of Chinese/Indian art to highlight the entire spectrum of Chinese Buddhist history. But even then, I think it would be helpful to identify the inspirations for each aspect rather than presenting it as an artistic Frankenstein.

Overall, I am glad that these sacred artifacts are being maintained and well-preserved, but I do think there is a lot more to do for this to become educational. Sightseeing brings visitors, but once they’re in the door, there needs to be much more to give them a sense of new perspective and understanding. Only then will they leave with piqued curiosity and appreciation.